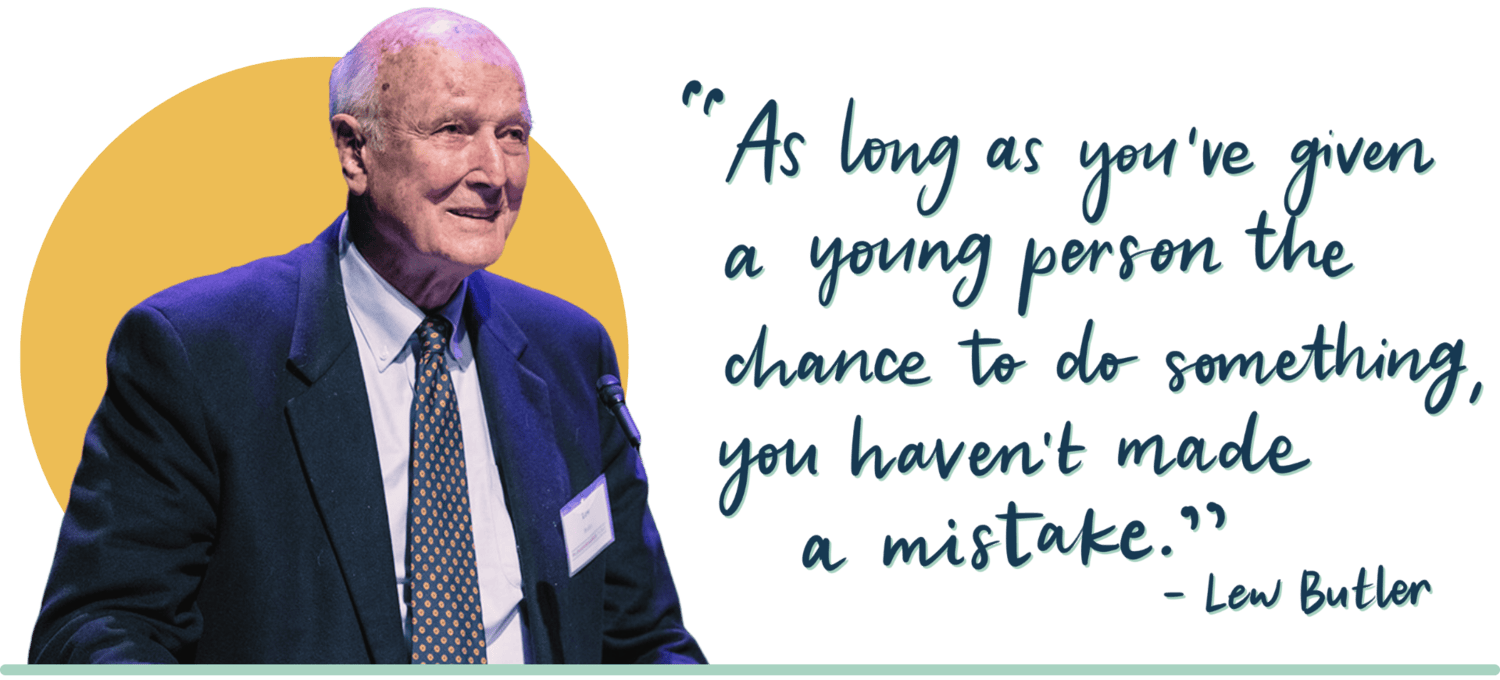

Lewis H. Butler (1927-2024)

There have been and will be many pieces written about Lew and his many professional accomplishments. I’ll leave that work to others and for now, focus on the personal.

Lew was already 79-years-old when I first met him 18 years ago. I was at the beginning of my career and had been awarded a mysterious fellowship that came with a year-long placement at an organization where I was to be mentored by an Executive Director. The fellowship also came with an oral history—a story about a man named Lew Butler and his “great mentor in life” Dan Koshland. There was no program, no structure, no goals, no agenda. And I had no clue what I was doing. Early in my tenure, Lew came to meet with me at the office. Sitting across from Lew at a long table, he asked, “Tell me about yourself” and it all came pouring out in a jumbled mess… I lacked a well-designed ambition or plan, but was hungry, literally and figuratively, and eager to take any opportunity that would get me closer to being able to work for social justice. Despite the fact that on the surface we seemed dissimilar in every way possible, Lew in his wisdom recognized something in me that day. We had a common spark.

In the coming years, Lew would become a profoundly influential force in my life. He stepped into many roles–part father figure, advocate, minister, supporter, friend, and the best cheerleader I’ve ever had. He was more than just a colleague; Lew was, and is, my mentor in life.

Lew’s Legacy

Lew came from a time when there wasn’t the bevy of terms we have today to describe our movement building work. He didn’t rely on a theory of change, metrics, or data analysis, rather his orientation was one of common sense and a genuine love of people who had dedicated themselves to what he called “public service.” Way before most philanthropists had caught up with the idea, Lew thought the best idea for changing the world was to find leaders who were grounded in community and support their leadership—without fuss, without self-aggrandizing. He also well understood from having worked across so many sectors and fields that what he called “community leaders” were best positioned not only to address the immediate concerns of their own people, but that by facilitating collaboration, they could tackle issues across many boundaries.

Lew would hardly recognize the terminology we use at People Power, but our work is an extension of his legacy. People Power specializes in serving leaders and organizations with a commitment to collective liberation. We share in this work and also in its promise: that by collaborating together to challenge interconnected systems of oppression, it is possible to create the kind of world we want to live in—a place of abundance and well-being where everyone is seen and supported in their full humanity.

Lessons from Lew

It’s such a comfort in this time of loss to have good work and a purpose to carry forward. As I’ve moved through these last two weeks of loss, I’ve been thinking of Lew and some of his distinctive characteristics that I’m continuously seeking to integrate into my own work:

Embrace Risk

Lew instinctively understood that the role of those with privilege in any situation was exercise and absorb risk on behalf of others. He used his positional power to push philanthropy outside of its comfort zone and threw his weight behind leaders who were unknown and unproven, but whom he sensed would do what he called “great things” if they were connected to resources. I remember him saying to me once when I was fretting over something I perceived to be going wrong, “As long as you’ve given a young person the chance to do something, you haven’t made a mistake.”

He stepped up to take on some of the most ambitious and seemingly impossible projects, fully knowing that the likelihood of public failure was high, going off on each new adventure with trademark optimism: “no is the prelude to yes.” Lew had many more stories that ended in some variation of “what a flop” “it didn’t work out” “they beat us anyway” that he did ones that ended with “it was a great success” (though there were those too!). Over a long lifetime, one can see how the ideas, relationships, and energy created by these initiatives weren’t ultimately a “total disaster” but rather the bits and pieces that would carry on into the next iteration, either adopted in full or altered by new leaders who benefited from the opportunity to learn from the past.

Stay Humble

Lew was an exceptional storyteller and many of his tales were told in such a way as to minimize his role in any achievements and maximize his role when it came to taking responsibility for mistakes. Some of these stories were fun and lighthearted. Others were heavy, bringing tears to his eyes in the retelling. I learned so much from him about leadership from the way he modeled humility. This was yet another way in which he used his privilege to benefit others—in normalizing failure as an essential part of leadership, he drew younger people to him. It’s no wonder that emerging leaders who tend to interpret their anxiousness as a sign that they are “imposters” would find comfort in his example. If Lew as a celebrated elder was still carrying the emotional weight of a misstep that had occurred decades previously, then maybe I’m alright?

I asked him once why he valued humility so much. He replied, “The moment you start thinking you know everything is right when you’re about to get yourself into big trouble.” He was always learning, always expanding. He looked to others often for advice and guidance on projects for which he had expertise, using these conversations as an opportunity to generate community and build others’ leadership. And on those things he felt were out of his area of knowledge, he would exclaim, “What would I know about that? Us old people should get out of the way. Let’s find a young person to lead this,” thus using his power to pass on opportunities to others.

Build Community

Lew genuinely loved people. He gave you that love before you earned it, meeting people with a sense of curiosity, he always found something nice to say about you. It felt good to be around him, so it’s no surprise that he had many friends across a broad intergenerational network. He was generous with these connections, always looking for people he could bring together to further common causes. He well understood the role of supportive relationships in making it possible for leaders to move their agendas and took special care in connecting emerging leaders with funders and other influential people that they otherwise would not have been able to access.

And because Lew loved people and was so optimistic about the potential for positive change, he was intolerant of those who did not do the right thing. Those who hoarded power, sought to exploit others, or used their wealth to push agendas that did not serve the common good, could expect a stern talking to that would escalate to a demand for change if not properly heeded. Just as Lew was very talented in bringing together groups to work on generative projects together, he was just as capable of organizing against something he saw as unjust. There are many colorful stories of the campaigns he waged against various bad actors, some won and some lost, but all building community along the way.

This community Lew built is woven throughout all he did and is central to the stories I shared above. Each of these people have also had a profound impact on my own life. I’d like to especially note the role of Dan Koshland and his grandson Bob Friedman played in shaping Lew as a mentor. Also of special mention, is my Butler Koshland Fellowship mentor, Malcolm Margolin, and our entire fellowship family, many of whom shared lifelong friendships with Lew.

Written by Kate Brumage, Former Executive Director, Butler Koshland Fellowships, & Executive Director, People Power, June 10, 2024